Joy Shows Her Finest

Lessons on Goodness from the Basketball Court and Beyond

And God saw everything that was created, and, indeed, it was very good.

Translation inspired by Genesis 1:31 (The New Interpreters’ Study Bible)

I stand at center court in an old, smelly elementary school gym as eight first-grade boys stand along the baseline, squirming with energy, desperate to move.

“When I blow the whistle, I’ll start dribbling and you’ll chase me, and whoever gets the ball first, wins!” I instruct.

We take a collective deep breath.

I blow the whistle, bouncing the ball against the beige floor.

A pack of puppies chasing their mama, yelling and laughing, squealing and panting, we move around the court with zeal.

I smile the entire time. I am simultaneously startled out of myself and wrested back into the deepest parts of me.

I matter only because we matter, and here on this basketball court, joy shows her finest.

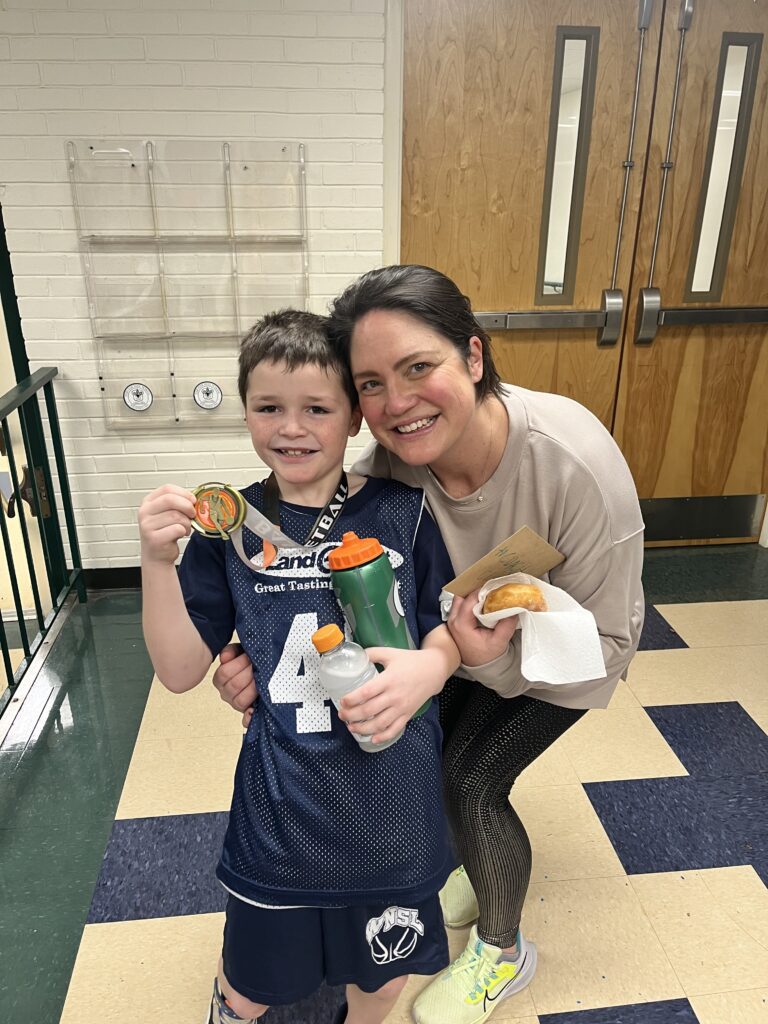

My kid jumps on my back, trying to pull me down, while his teammate wrangles the ball away from me. We gently fall to the ground, breath heavy, laughter loud.

I roll myself up to standing and say, “Teamwork! Everyone wins!”

They groan because they want a winner, a clear answer, some certainty. I won’t give that to them because you can’t give something you don’t have. Instead, I serve up a plate of love with a side of jubilance and send them on a water break.

It’s now a regular part of practice—the chasing, the playing, the running, the trying to get the ball from Coach Claire. It gets our blood moving and our laughter flowing, even and especially on the nights when emotions run high and kindness doesn’t always abound.

In the span of an hour, one kid throws the ball into another kid’s face (intentionally), another one calls another one a loser, and still others get frustrated and start to lay blame.

“If only he dribbled better, I would’ve made my shot.”

In the span of an hour, we show our humanity in its fullest. And?

We are still good.

To the kid who throws the ball in another kid’s face, I say, “You’re a good kid having a hard time. Let’s take a water break, breathe deeply, and come back when we no longer feel like we need to throw balls at people, okay?”

I’m able to say this to my player because I heed the words of Dr. Becky Kennedy, known as the “millennial parenting expert” and author of the bestselling book, Good Inside: A Guide to Becoming the Parent You Want to Be. The mantra she preaches and teaches is “Your kid is a good kid having a hard time.” Her teaching echoes God at the beginning of time who gazed upon creation and called it good.

To the kid upset because someone called him a loser, I say, “Do you know who you are?”

The kid nods, “Yes.”

“Do you know you’re not a loser?”

“Yes.”

“Knowing who you are is the most important thing,” I say. Then I ask again, “Do you know who you are?”

“Yes. I’m good!”

“Amen.”

And to the ones ready to lay blame, I pause and say, “Let’s take a minute to sit still with our frustration. Let’s breathe. Let’s touch our hearts and connect with the compassion and goodness that’s inside all of us.”

The kids look at me like I’m speaking a foreign language because to many of them, I am.

In fact, it often feels like learning a new language to me, too.

I grew up with the language of “Suck it up and get back out there” on the basketball court and in life. So when I have a kid who’s crying and hurt, I, too, have to touch my heart, take deep breaths, drink some water, and then speak the language of love and goodness instead of blame and rigidity.

On the drive home from practice as my kid plays Pokemon Go in the backseat, I wonder how we strayed so far from knowing our inner goodness. Perhaps the image of God sitting high apart from us instead of rolling around in the dirt (or on the court) with us is a start. The more separated we are from God, the more separated we become from ourselves.

The traditional creation stories position God as sitting on high, looking down, surveying the created world. God is separate from it rather than a part of it, disconnected from it rather than a companion with it. The traditional stories make creation sterile and objective rather than messy and particular.

Yet God was neither sitting above nor looking down when creation appeared. God would rather be in the messy middle than ruling from on high. Goodness is not something that is created; rather, it is an inherent reality of creation. To be created is to be good.

The more we place God on a pedestal, the harder we make it for us (or anyone else) to reach that pedestal. Therefore, rules and systems get created, further removing us from the God who danced in the dirt with us and knew we were good from the beginning. But before we succeeded or achieved, before we learned how to dribble or make a shot, before we did anything, we were good.

Therefore, goodness is not something to achieve, climb towards, or reach. Rather, goodness is within us, and it is our birthright. This, of course, is what Dr. Becky proclaims from a psychological and systems perspective in regards to parenting, and it’s what I want to proclaim as a theological framework for parenting (and human-ing), as well.

If we start with the understanding that we are good, then we’re less likely to berate ourselves (and our kids) over every little thing that feels awry. If we take a beat to imagine God at the beginning of time creating us in the dirt, then we might be less likely to think of God as a place to arrive and more likely to think of God as the Good that lives and breathes inside of us from the start.

As I begin to believe this for myself, I can then begin to believe it for every other person with whom I share this life.

To be created is to be good.

In the beginning there was goodness. It was not achieved nor mastered. It simply was and is and forever will be. The beginning, middle, and end meet in God, and the messiness of the meeting is good.

The more you get in touch with your goodness, the more you’ll get in touch with the goodness of the people around you, and your flourishing will be palpable, and your kindness will overflow.

To be created is to be good. You are good. We are good. May it ever be so. Amen.

Claire K. McKeever-Burgett serves as an Assistant Theology Editor for The Other Journal and is the Director of Communications and Employee Relations for the Nashville Collaborative Counseling Center. Former host of the award-winning Academy Podcast, Claire is ordained clergy, leader of contemplative spirituality offerings, mother, certified birth and postpartum doula, yoga, dance, and martial arts instructor, partner, lover, volunteer basketball coach, and friend. Her first and forthcoming book with Chalice Press centers ten stories of women from the Gospels in their words, with their own names, interwoven with her personal story of growing up as a woman with a vision and a voice in a conservative, Southern Baptist, male-dominated world. Claire lives in Nashville, TN, with her partner, Adam, and their two children, Wade and Liv.